Problems with Manifold's Loan System

And: in favour of interest payments

This piece argues that interest payments solve miscalibration from discount rates on Manifold better than the current loan system.

The basic problem is that considerations of opportunity cost reduce the value of betting on long-term markets, or those near 0% or 100%, making markets miscalibrated. The loan system reduces some of the opportunity cost of trading, but not all, because the initial cost of the bet always exceeds the loaned amount, and the cost comes earlier. Interest payments solve this by compensating for time value, not just reducing the cost. With interest payments, it is possible for a fair bet to remain fair even if you discount future profits, and this is not possible with loans. The system is also simple, easy to understand, and matches what other prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket do.

Discounting and prediction markets

Most introductions to prediction markets go something like this: contracts are worth $1 if the event happens, and nothing otherwise. If you think the event has a probability p of occurring, then the expected value is p.

So if the price of the contract is less than p, you can buy and profit in expectation. When everyone does this, wisdom of crowds, truth machine, etc.

What this analysis misses is that in prediction markets, the cost is incurred now, but the payoff is later. Since money later is worth less than money now, that means the cost is weighted more than the benefit.

If you weight future payoffs by some number δ, between 0 and 1, then the expected value of the contract is not p, but instead δp, which is lower. But the cost is now - it gets full weight. So even if you think the market price is too low (high), it still may be negative expected value to buy ‘yes’ (‘no’).

Discounting has the strongest effects on markets at extreme prices, near 0% or 100%. The gap between the discounted value δp and the un-discounted value p widens the higher one’s belief p. Thus we see a 3% chance of Jesus returning in 2026, or whatever.

Discounting affects pricing in nearly all financial markets. Cash-settled futures are priced according to the expected value of the underlying security, but always at a discount, since the futures’ payoff is, appropriately, in the future.1

But if the point of prediction markets is to provide probability estimates on important questions, then discounting is an issue, because it makes prices deviate from probabilities in predictable ways.

Manifold’s current approach: loans

To address the miscalibration induced by discounting, Manifold lets users take loans on mana they have bet. Each day, some proportion of the cost the bet (specifically 1 per cent of the remaining capital locked, or 0.01*0.99^(t-1) per cent of the cost, where t is the number of days since the bet was placed) is returned to the user. When the bet pays off, the user pays back the amount they borrowed (which is (1-0.99^T) per cent of the cost, where T is the total number of days).

By giving users a benefit each day, and pushing the cost (repaying the loans) back until payoff, loans do help somewhat.

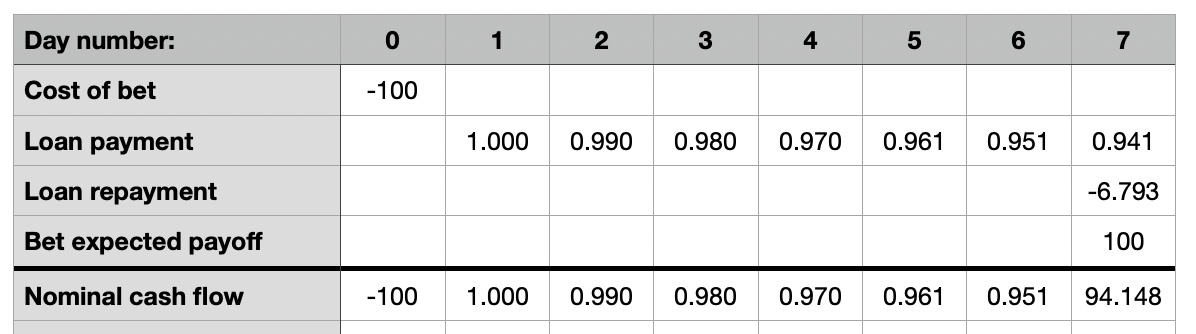

To see this, let’s imagine a bet. For ease, say I bet on a fair coin flip at 50%, which pays off in a week. I spend 100 mana today (day zero), and expect to receive 100 mana on day 7 (50% I win 200, 50% I win nothing). In the mean time, Manifold pays me 1-0.99^(t-1) for days one to seven, and I pay back the total amount loaned on day seven (which is 1-(0.99^7) = 6.8% of my initial investment, or 6.8 mana).

My cash flows look like this:

Suppose that I discount future cash flows by δ per day (so by day 7, I am discounting by δ^7). Then the discounted, expected value of this transaction is just the discounted sum of all these nominal cash flows. More specifically:

If we use a discount factor of δ=0.99, the value of this transaction turns out to be -6.6 mana. It’s negative, because we’re taking a bet with no edge and we discount future payoffs (and the 1% loans don’t overcome our discounting).

But let’s compare to the case where we don’t receive loan payments at all. Then we simply have:

With δ=0.99 this evaluates to -6.8 mana. So having loans increased the discounted expected value of the bet by about 0.2 mana. Loans help!

But not by much, and they don’t solve the problem. Even though my bet was zero nominal expected value, even with loans, the bet negative discounted expected value. The loans weren’t enough to overcome our discounting.

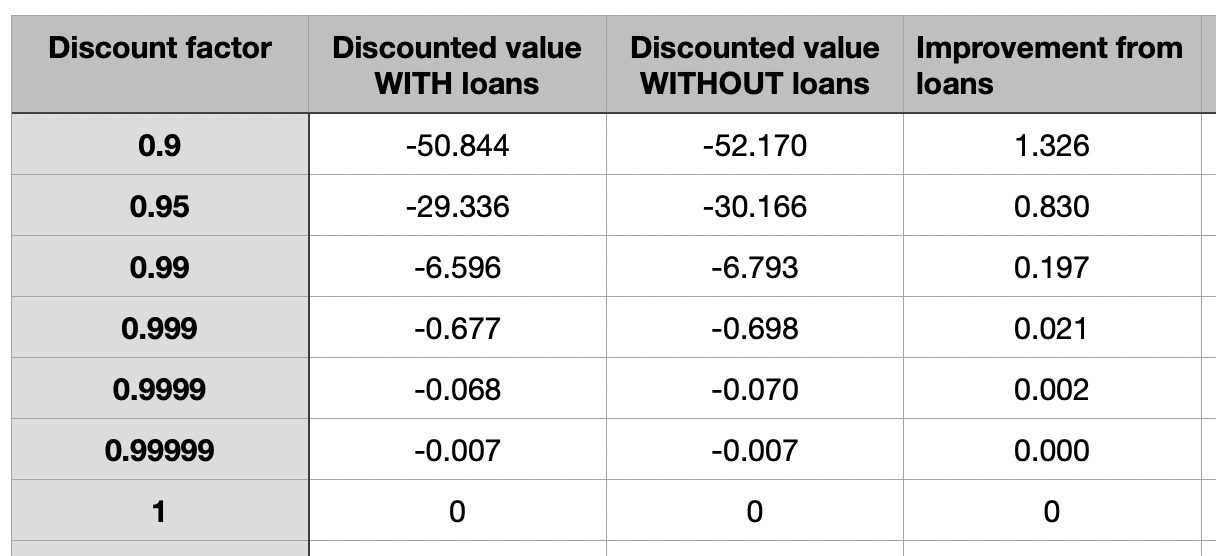

This is not just because δ=0.99 is too aggressive a discount factor. Even if I chose 0.999, or 0.99999999999, the discounted expected value of the bet would STILL be negative with loans:

This is ultimately because loans do not add value if you are perfectly patient (δ=1). All loans do is shift payments across time. If you do not care when payments occur, loans do not add anything.

For the perfectly patient trader, a zero-EV bet is still zero-EV with loans.

But the more future payoffs are discounted, the less value there is to any bet, even with loans. This is because the initial cost of the bet always exceeds the amount received in loans, and the cost comes earlier.

Thus even with loans, any discounting turns a nominally fair bet to negative EV.

I’ve used a fair bet here to make the maths easier, but the general point holds - even with loans, discounting reduces the value of a bet no matter what. It makes positive EV bets less positive, or perhaps negative.

Increasing the loan rate to 2% or 5% or 10% does not solve the issue. The only way to solve this with a loan system is for 100% of the cost of the bet to be returned to the trader instantly, which is then paid back at expiry - in essence, the cost is only incurred once payoff arrives.2

Alternative: interest payments

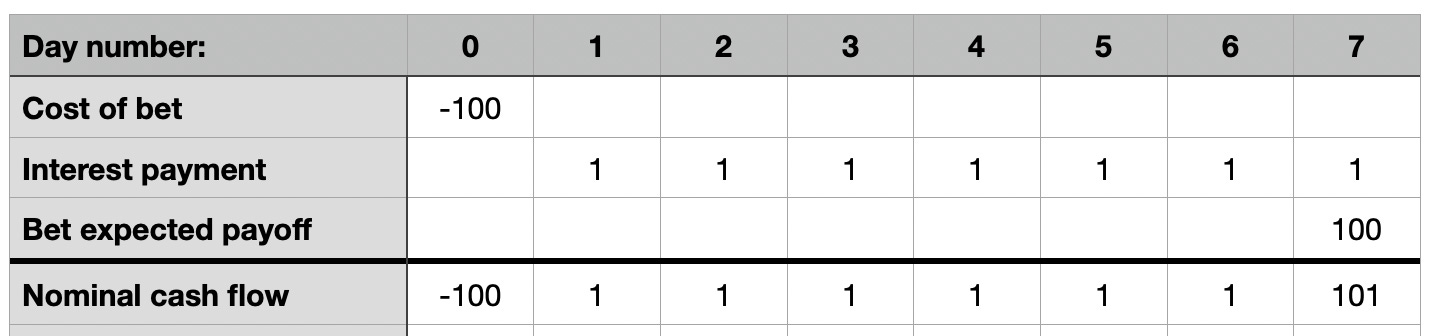

Suppose Manifold used interest payments instead. Here, the trader takes a position, and (say) 1% of the value of that position is paid each day. This is new mana, that didn’t exist before. The interest does not compound (unless the trader reinvests into the market). Using our 100-mana-on-a-coin-flip example, the cash flows are:

With a daily discount factor of δ, the value of the bet is:

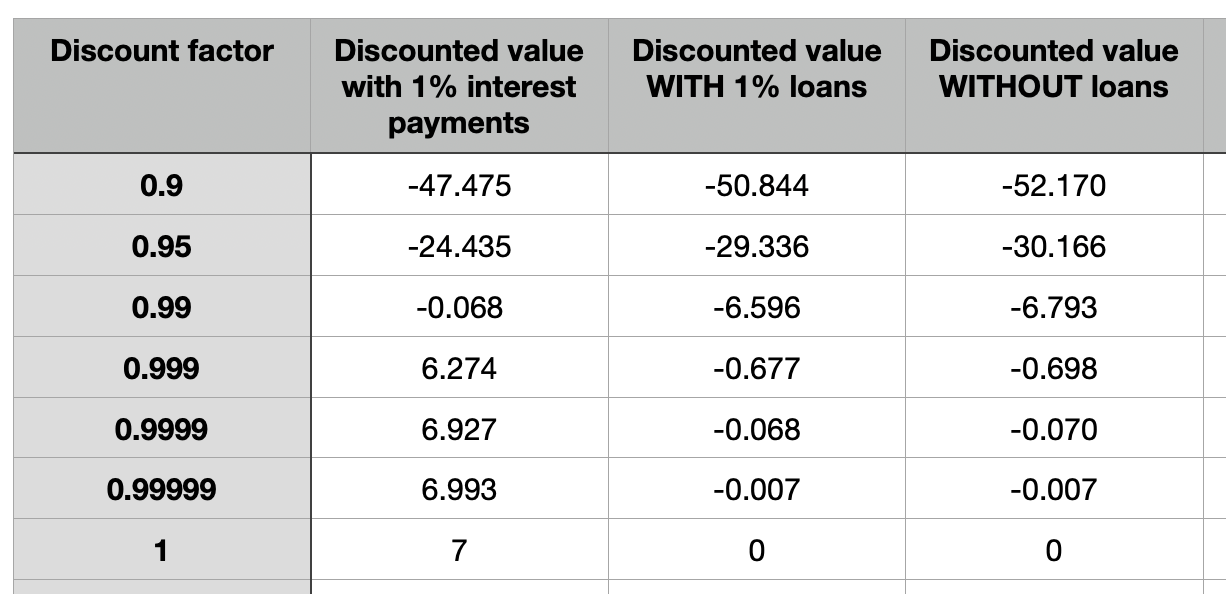

With a discount factor of δ=0.99, this evaluates to -0.07. Much better than the -6.6 we got with loans! And, unlike loans, it is now possible for the bet to have zero discounted expected value (matching its un-discounted value) even if we discount. This occurs precisely when δ=1/(1.01).

As the discount factor approaches 1, the value of the bet approaches the nominal value of the interest payments. In all cases, the value of the bet exceeds the value it has with the loans system:

Notice that with interest payments, it is possible for a fair bet to remain fair even if you discount future profits, and this is not possible with loans.

The reason is that interest payments compensate for time value, while loans only reduce the cost (and never to zero, unless loan rates are 100%).

Implementation

With interest payments, it’s still possible for a fair-bet to be negative EV, if your discount rate is high enough. This is always going to be the case for any system. Different people come to Manifold with different discount rates - a cracked bettor has a larger opportunity cost than a mid bettor, and independently of opportunity cost, people vary in their patience. To fully solve this, you would need individualised interest rates that match people’s individual discount rates.

This is hard to do exactly, but I think a good approximation would be if Manifold implemented tiered interest rates by net worth. Say, those with under 10k net worth earn 30% interest, and people above 1 million net worth earn 3% interest. This would correctly compensate traders more when capital constraints are bigger. The ability to do something like this is a big advantage of using play money. It would reduce the mana-supply-inflation that would result from interest payments, since big accounts earn less. And it would even incentivise whales to loan out to smaller accounts at rates favourable to both of them, getting new users to bet more.

I would also argue that interest should only be paid on investments, not balances. A huge amount of the mana supply is sitting unused in the accounts of whales, either because they left the site or there simply aren’t enough positive EV opportunities to make use of it. With interest payments only on investments, it is suddenly preferable to sink your net worth into markets expiring in 2030, or markets trading at 99%, and at least put the mana to some use. It incentivises doing something with your mana, even just coin flip it, rather than having it sit idle doing nothing.

I’m not too sure whether interest should be paid on the market value of positions, or the initial investments. If the former, the time at which interest is calculated should be randomised to prevent gaming (imagine interest was always paid at exactly 9pm: you build a position at 1% in a random market, buy it up to 99% at 8:59pm, collect the interest, and sell back at 9:01pm).

In futures and other derivatives pricing, positive discount rates tend to uniformly bring prices down relative to the nominal expected value of the contract. Prediction markets are more interesting, because the direction of the bias depends on the price - downward bias for markets above 50%, and upward bias for markets below 50%. This stems from the fact that in prediction markets, both sides of the transaction fully collateralise their position, whereas in futures markets, the seller essentially offers the buyer a loan (in the form of leveraged exposure), for which they are compensated with implicit interest payments. In fact, one can create a synthetic bond by selling futures while acquiring equal exposure in the underlying. You cannot achieve the same thing in prediction markets by buying ‘yes’ and ‘no’ at the same time.

This is how most casual bets between individuals work, where time value considerations aren’t an issue. If I bet my $1000 to your $1000 that I have solved Navier Stokes, neither of us locks up the cash anywhere - the money stays in our bank accounts or in assets or whatever. Once the bet is settled, one of us pays the other. There was no opportunity cost involved, because we didn’t have to collateralise our positions. It’s as if we both bet against each other in a prediction market, then took out a 100% zero-interest loan on the collateral.